Looking for help? 1800 880 569

No one wants to think about their own death or decline, but these things are inevitable. Although we can’t choose how and when we die or become incapacitated, we can make some important choices about what happens to us when that time does come. Everyone has different values and beliefs when it comes to end-of-life care. Some people want their life saved at any cost while others prefer little or no intervention. Some people want to donate their organs or have their body donated for medical research, but this is anathema to many religions and belief systems.

Depending on the circumstances surrounding your severe illness or death, you may lose the capacity to make decisions about your own care and someone will need to make those decisions for you; that someone could be a spouse, a child, a sibling or a friend and the burden of those decisions is often enormous. Will they know what you want? Will they be able to follow through with your wishes?

Having an advanced care plan could help to eliminate the stressful decision-making around your medical care if you are temporarily or permanently unable to make those choices for yourself.

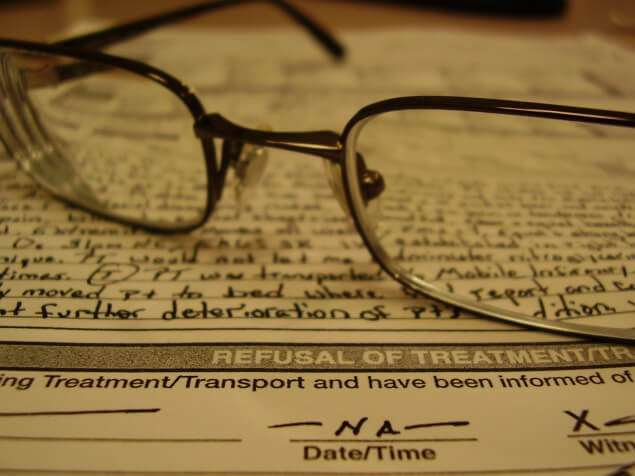

An advanced care plan, or living will, is a document written voluntary by an individual that outlines the types, conditions and preferences for medical care that they would prefer be given, prior to needing medical or palliative care.

An advanced care plan can also indicate who is responsible for making decisions about your care on your behalf, in conjunction with a Power of Attorney/Enduring Guardianship.

If you are incapable of making medical decisions and do not have an advanced care plan (sometimes referred to as an advanced health directive), your doctor will make the necessary medical treatment decisions for you. These may include life-saving or other measures that you do not want.

According to the Australian Human Rights commission, living wills/advanced care plans are not legally binding, however they may be given legal recognition in certain circumstances. For example, if a dispute over care arises (say between a son and a daughter over the choice of care for their ailing parent), a living will could be used as evidence by a Guardianship Board, tribunal or court to make a decision regarding medical treatment.

Part of preparing an advanced care plan is to determine who you want to make medical decisions on your behalf if or when you are unable to do so. In many cases this may be a spouse, but it doesn’t have to be. In fact, even if you have a spouse, you may not want them to be burdened by the pressure of medical decision-making on your behalf. How emotionally difficult would it be for them to be solely responsible for making critical and, sometimes, final choices about your medical care?

Additionally, you and your spouse may not see ‘eye-to-eye’ when it comes to medical preferences. What if you’d prefer no intervention but they want to do whatever it takes to keep you alive? Or what if your spouse is unwell too? Will they be able to handle making the necessary decisions about your health care? Appointing an alternative responsible person (Enduring Guardian), may alleviate some of the tension and anxiety in these circumstances.

An Enduring Guardian can be anyone – another relative or a friend. An Enduring Power of Guardianship (known also as a Power of Attorney) is a legal document that authorises a person to be responsible for making critical personal, lifestyle and medical choices on your behalf.

In terms of advanced care plans, we’re not always talking about end-of-life medical choices, like life support. You may become incapacitated long before physical death – this is especially the case in relation to Alzheimer’s, dementia and other neurological diseases.

You may be physically capable, but mentally unable to make sound decisions for your own care, as may be the case for a patient with mid-to-late stage Alzheimer’s. In these instances, your Enduring Guardian could arrange for in-home nursing support or may need to make the decision to have you moved into a specialised care facility.

An Enduring Power of Guardianship (EPG) allows you to be very specific about the scope and application of the authority given to your Enduring Guardian. You could give them carte blanche, but more than likely, you’ll have some preferences that will help to shape the EPG.

If you have an EPG, it can work in conjunction with an advanced care plan, but you don’t need an EPG to have an advanced care plan.

EPG legislation varies slightly by state, so make sure you check with your local authority as to the requirements and specifications of your state.

So, how do you go about writing an advanced care plan? The most important thing to do is to start by thinking about what you want your advanced care plan to cover. This is, ultimately, quite complicated but we’ve broken it down into a few more manageable sections.

You can decide when and if you want to receive life-sustaining measures and under what circumstances.

You may ask for life-sustaining measures to be withheld or ceased if you have a terminal illness, severe or irreversible brain damage or an injury or illness from which you will not recover. This is known as a DNR, or Do Not Resuscitate.

Your advanced care plan doesn’t just cover medical preferences. It can also provide your family/Enduring Guardian guidance on how you would like to be treated in certain situations, like if you begin to suffer from dementia, and you would prefer being placed in a specialised care facility instead of being cared for by family members.

Although around 70% of people want to die at home, only around 14% actually do, while approximately 50% die in hospitals. Put your preference in your advanced care plan – that way, if it’s suitable to do so, your family may be able to support your last wishes.

Organ donation is often a sensitive and emotional subject that, if not discussed beforehand, may put your family and loved ones in a difficult position when your time comes.

If you want to be an organ donor, make sure your family know that this is your preference. Although you can choose to be an organ donor by selecting it on your driver’s license or registering on the Australian Organ Donor Register, this is only a record of your preference. Your family (or Enduring Guardian) have the final say as to whether or not your organs and/or tissues are donated.

If you’re confused by the different levels of medical care available or any health related jargon, consider discussing your options with your doctor – they will be able to provide you with comprehensive information on what different types of care actually mean and what sorts of medical procedures are involved.

Most importantly, talk to your family and loved ones about the details of your advanced care plan. No one wants to have these types of conversations, but a little bit of discomfort or sadness upfront may save a lot of stress and heartache for your family in the future.

Thorough preparation is key to helping your family face these difficult situations, there are other ways to make your family feel reassured about the future, such as comparing life insurance providers in order to obtain a policy that will endure beyond a disability or be there in the event of your death. It could mean the difference between maintaining your family’s quality of life or suddenly finding that everything will change for the worse for them.

Don’t leave advanced care planning too late; although we tend to associate death with the elderly, it may happen much earlier in life. You can help protect your choices and your family from difficult decisions related to your health care with an advanced care plan that makes you feel at peace with your wishes.