The Burrow

In our animation, the last 10 decades demonstrate that when it comes to the fastest production (road-legal) cars in history, brands have shifted gear. New developments in aerodynamic engineering, horsepower and manufacturing meant they could push performance further and faster over time.

It’s hard to find places where you can legally go that fast on the road – plus, you likely won’t be covered by car insurance if anything happened while driving at those speeds – but it’s amazing to see just how powerful sportscars have become.

As experts in comprehensive car insurance, we’re passionate about all things car and have a keen interest in trends and changes. So, we identified some of the fastest production cars of the last 100 years, and combined the three to five fastest cars released every five years to create a hybrid design, reflecting an ‘average shape’ of those sports cars. The horsepower and speed figures are also averaged based on each car that went into the hybrid design.

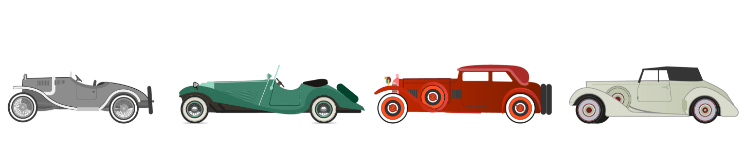

By the time our video begins, the horse and carriage were already replaced. The sports cars of the day combined simplicity with elegance, creating their own unique, timeless, evocative style. Brands like Bentley, Stutz Motor Company, Duesenberg and Amilcar lit the path for faster supercars by producing sporting road cars capable of speeds over 100kph (60mzph), even with only 70 horsepower.

In the 1920s, fast road-legal production cars had between 50 and 70 horsepower.

Modern supercars have over 30 times that amount of power.

The supercars of today (the cream of which are known as hypercars) are designed to turn heads just as much as they’re made to burn treads. These cars demand to be appreciated (when they’re going slow enough for pedestrians to catch a glimpse) with aggressive lines, dynamic angles, and large amounts of framework cut away.

These bold forms aren’t just for looks, but to also make them as aerodynamic as possible.

Today, manufacturers like Aston Martin, McLaren, Koenigsegg and Bugatti carry the torch with some of the fastest and most powerful road cars in history.

So, how have we gone from the understated elegance of the Stutz Series K to the powerful and sleek form of the McLaren Speedtail? Let’s take a step through time.

Our timeline begins with the ‘20s when sports cars were a statement in elegance. The hood opened up sideways rather than the front, unlike most modern cars. Seats were often stately, leather affairs mostly designed for multiple people to sit together, rather than the individual seats of today. Engines ranged from four to eight cylinders, with two or more valves per cylinder.

Thus, models like the Bentley 3 Litre, Duesenberg Model J or Rolls-Royce Phantom Jonckheere Coupe are timeless pieces of art as much as they are road cruising machines capable of speeds over 100kph (70mph).

These are the types of cars that today are covered by vintage and veteran car insurance policies – specialist policies for these unique pieces of history.

Headed to Gooding & Co.’s 2020 Scottsdale, Arizona, auction, the 1925 Lancia Lambda Torpedo is an excellent example of a highly advanced, hugely significant model that was years ahead of its time.https://t.co/Wnv195FH8L

— Autoweek (@AutoweekUSA) January 13, 2020

Rolls-Royce Phantom Jonckheere Coupé at our debut event at Windsor Castle pic.twitter.com/m0ETLktTEj

— Concours of Elegance (@ConcoursUK) January 12, 2017

Made in United Kingdom Bentley 3 Litre ( 1921—1929 ) pic.twitter.com/PA6Xt7Fag2

— Made in … (@Nik333Alex) May 8, 2018

The ‘30s saw a refinement of the stylings exhibited in the ‘20s, and gave the world timeless models like the Bugatti Type 57, Bentley 8 Litre Gurney Nutting Sports Tourer, Jaguar SS 100 and Mercedes-Benz 500K.

via Classic Car Club of America

This 1937 Bugatti Type 57 with Stelvio coachwork by Gangloff is powered by a 135 bhp 3.3 liter dual overhead cam inline eight-cylinder engine with four-speed Cotal

Read more: https://t.co/fxRI1vWX3V pic.twitter.com/lWPrHL5Zcw— Oldtimer ClassicCars (@spicker123) September 16, 2019

This 1931 Bentley 8 Litre Gurney Nutting Sports Tourer won Best of Show at the 2019 Pebble Beach Concours today. Photo taken during Thursday’s tour. #pebblebeachconcours pic.twitter.com/8iVNVibEy4

— tim huntington (@timhuntington) August 19, 2019

Interestingly, a unique run of Bugatti Type 57C Atlantics (produced in 1936), of which only four were made, saw one of them disappear in 1941, just before the height of World War II. To this day, no one knows where it is and what happened to it.

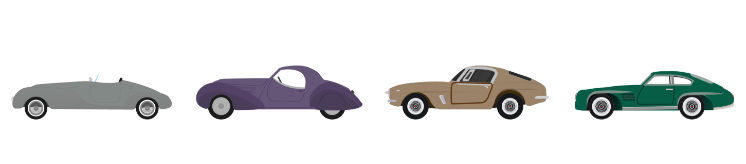

The ‘40s saw speedy automobiles, such as the Aston Martin Atom, Jaguar XK120 and Healey Silverstone, become more curved with smoother fronts, shapes and lines to minimise wind drag. These cars’ bodies also sat lower to the road, and they grew wider to make room for larger, more powerful engines like the Jaguar’s 1970CC twin carburettor heart or the six cylinder dual overhead camshaft XK6 engine used on the Jaguar XK120.

An important concept car in the history of Aston Martin, the ‘Atom’, completed in Spring 1940, was ground-breaking in its design and engineering. Sir David Brown was said to be that impressed with his test drive in the Atom that it aided his decision to purchase Aston Martin. pic.twitter.com/PxuwnVmhNa

— Aston Martin Works (@AstonMartinWork) March 5, 2018

Healey Silverstone –#Healey #Silverstone #HealeySilverstone #ClassicCar #Vintagecar #Klassiker #Roadster #Sportscar #Oldtimer #Vintage #VintageLegends pic.twitter.com/sj5izlshlm

— VintageLegends (@VintageLegends) December 15, 2019

Following this decade, the ‘50s continued the trend of smoothing out edges; it also saw the vertical grills of the past become wider to help cool the more powerful engines underneath so they could run further and faster, achieving speeds between 130kph and 220kph (80-130+mph).

The ‘60s beckoned the golden age of American muscle cars, like the Chevrolet Corvette C1, the 427 Stingray and Shelby Cobra – long, powerful cars designed to go fast in a straight line. These are the types of vehicles that come to mind when you hear the phrase ‘classic car’.

European brands produced agile roadsters with sleeker angles than the muscle cars and headlights that retreated into the car’s framework, further reducing wind drag to help the fastest production cars of this decade reach speeds over 270kph (170+mph) or more.

1960’s Shelby Cobra pic.twitter.com/gWJzmGcjxp

— History On Wheels (@HistoryOnWheels) January 21, 2015

This decade also saw the legendary motorsport battle between Ferrari and Ford. When Henry Ford II attempted to buy Ferrari, and Enzo Ferrari refused (as he would lose decision making power over Ferrari’s racing team), Ford decided to try and beat Ferrari at the Le Mans 24 hour race – which had been dominated by Ferrari’s racing team for years. After two years, the Ford GT40 MK II defeated the Italian stallion in 1966 – a legendary motorsport rivalry depicted on the silver screen in 2019.

The road-legal version of the Ford racer, the GT40 MK III, featured large vents in its hood to help air flow smoothly over the body to lower its aerodynamic drag co-efficient (the lower the drag co-efficient, the more the car ‘slips’ through the air).

Another motorsport rivalry from this decade includes Ferrari and Lamborghini. The story goes that Ferruccio Lamborghini, a talented Italian engineer who had established a successful tractor company, took his own Ferrari 250 GT to get serviced at Ferrari’s headquarters. He complained about the clutch to Ezno Ferrari himself.

Enzo Ferrari then dismissed Ferrucio Lamborghini, insulting his engineering skills. Ferrucio then began working on his own sports car, and in 1963, Automobili Lamborghini was born.

Another famous call out from this time period includes the Aston Martin DB5, which was made more popular by its appearance in the third James Bond film, Goldfinger, in 1964.

The DB5 is back.

Limited to 25 models, our DB5 Goldfinger Continuation cars are being created at Aston Martin Works in Newport Pagnell and carefully crafted recreations of the iconic model from the original movie.

Find out more: https://t.co/V5RDp32v5R#DB5 #AstonMartin pic.twitter.com/I9BjwxYG9B

— Aston Martin (@astonmartin) March 20, 2020

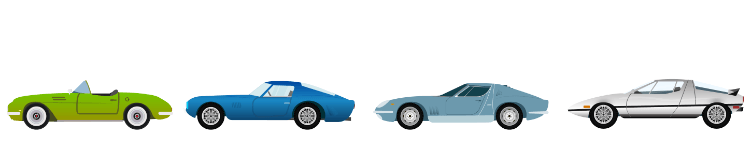

Fast sports cars of the ‘70s, like the De Tomaso Pantera and BMW 1M, were typified by large, long, sleek bonnets and short rear trunks; stylings typical of the classic car era. Their windscreens were also angled acutely to reduce aerodynamic drag. Anyone lucky enough to own one of these beauties today would need to find an adequate classic car insurance policy, as generic policies are not designed for such powerful machines of the era.

However, the age of the classic car was not to last. Increasing emissions controls had a knock-on effect on the average top speed of some of the newer fast cars of this decade, particularly muscle cars, causing another downwards turn in our animation.

LEVEL: PLAYER – 1972 De Tomaso Pantera by Wouter Gillioen from @howestDAE https://t.co/XesJbrfOBm

#3dsmax pic.twitter.com/oPrEdlmdy8

— TheRookiesCO (@TheRookiesCO) March 31, 2020

Stunning #BMW M1 Procar restored by Canepa Motorsports https://t.co/ynskZT7gCm pic.twitter.com/5gsvBHYNTI

— Cars Autos Rides (@CarsAutosRides) March 30, 2020

Some beastly supercars of the ‘80s, including the Isdera Imperator 108i, Ferrari F40, and the Lamborghini Countach LP5000 QV, resembled spaceships as much as road cars. This decade saw rear spoilers become fashionable not just for their sci-fi looks but also increased downforce – providing more grip so cars could travel faster around corners.

Lamborghini Countach LP5000 QV (1985 – 1988)

Engine: 5.2L V12

Power: 455 PS

Top Speed: 295 km/hMore information here: https://t.co/TQuhtkYUYn#lamborghini #italian #sportscar #supercar #80s pic.twitter.com/zJk9SaJ4DE

— More Cars (@more_cars_db) July 29, 2019

Rear ends grew larger on some models, and recessed side vents (also known as fender vents) became popular for their style and ability to relieve pressurised air, which improved stability.

The ‘80s spaceship design continued into the ‘90s, leading to eye-catching models, like the Lamborghini Diablo, Dauer 962 Le Mans, Jaguar XJ220, Ferrari F50 and Lotus Elise GT1, with the fastest of these reaching well over 300kph (200mph).

Cooler than cool: Dauer 962 Le Mans: https://t.co/adQRTpmso5 pic.twitter.com/Zsh7mbxFQt

— Wheelhangar (@wheelhangar) April 13, 2016

Today on http://t.co/bYugvlQvAp – The Jaguar XJ220 – #jaguar #british #car #supercar #design #luxury pic.twitter.com/Pwk4VGCNHX

— Silodrome (@Silodrome) September 24, 2015

Ferrari F50 pic.twitter.com/VOWqfl397Q

— Richard Tipper (@perfectionvalet) March 30, 2020

Car of the day: 1997 Lotus Elise GT1 pic.twitter.com/IkoITxucQa

— Steve Hasting (@durandurantulsa) August 10, 2016

Spoilers, vents, air intakes; if it could help make the car more aerodynamic, then supercar manufacturers were willing to give it a whirl. Some of the fastest road cars of this decade were so low to the ground there was barely any wheel arch left in the bodywork.

Stability was an issue in this decade. The Mercedes-Benz CLK GTR flipped over backwards at speeds of over 300kph (180mph) in 1999 on the Mulsanne straight at Le Mans. The same model had also ‘taken off’ twice previously, including one instance involving Australian racer Mark Webber.

The Mercedes-Benz CLK GTR Is One Of The Craziest V12-Powered Cars Ever Made https://t.co/L1qbEA4X9y pic.twitter.com/ReaaarUpDN

— Bobby Ore Motorsport (@OreBobby) April 27, 2018

Fortunately, all three drivers survived.

So, in regards to the Mercedes-Benz, what caused a state-of-the-art race car from the world’s most experienced car maker to suddenly lift up and somersault through the air at three different times?

Adrian Feeney, Chairman and CEO of the Society of Automotive Engineers – Australasia (SAE-A), says most theories agree that the car lifted a little at the front when cresting a hill, causing a pressure build-up underneath the car as the Mercedes followed a Toyota GT-One’s slipstream. (The road-legal version of the Toyota is one of the models incorporated into the 1995 car shape in our animation.)

Here’s a great Sunday morning read about one of the most wild road legal Toyota vehicles ever produced, the 1998 GT1-class homologation special, codenamed the TS020 and badged as the Toyota GT-One.

— McPhillips Toyota (@McPhilToyota) October 6, 2019

A ‘slipstream’ refers to the disturbed current of air behind a car. Driving in the slipstream can reduce drag, improve fuel efficiency, but it also affects lift and downforce.

Following the dramatic crashes – plus other similar events in racing during the late ‘90s – the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (International Federation of Automobiles) changed the rules, stating that race cars must have vents in the front bumper to relieve pressure build-up.

In 1999, The Ford Model T was declared the greatest car of the century, but nominations included the Mercedes 300SL, Audi Quattro, Jaguar XK120 and Chevrolet Corvette Stingray, all of which are included in the animation above.

Audi Quattro 1980 года pic.twitter.com/qhfdStORxB

— Wroom! (@wroom_news) March 27, 2020

Additionally, Italian designer Giorgetto Giugiara was named Car Designer of the Century. His handiwork includes the Ferrari 250 GT SWB Bertone and Lotus Esprit (which also made an appearance in a Bond film, The Spy Who Loved Me) – cousins of the Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta SWB and Lotus Esprit SE respectively, included in the video above.

At the turn of the millennium, cars became wider at the rear and angled slightly downwards; this design helped them to maintain a neutral or negative pitch angle – i.e. the car’s nose was closer to the ground than its rear, helping reduce any air pressure build-up. A new century also saw new contenders enter the race, such as Koenigsegg, Zenvo and Shelby SuperCars (SSC).

Cars like the Bugatti Veyron (the first Bugatti in almost 20 years since the EB110), SSC Ultimate Aero, Zenvo ST1, Koenigsegg Agera R and Hennessey Venom GT all brought more than 1,000 horsepower to bear on the road. In the early 2000’s, the fastest supercars and hypercars were able to reach speeds just over 400kph (250mph). In the late 2010’s, the fastest hypercars were recording speeds over 480kph. In 2019 the Bugatti Chiron was the first to break the 300mph barrier (490kph).1

Zenvo ST1 in action! Who’s ready for 2019?! #historide #checkmyhistoride #zenvost1 #2019 @adam_bornstein https://t.co/Kbu4jF84gU pic.twitter.com/MzWDEiM87g

— Historide (@historide) December 31, 2018

#GoalsOf2018 ride this beast

Hennessey Venom GT pic.twitter.com/fRyTTauqsA

— Rahe3l (@Supreme_RaheEl) December 30, 2017

These mighty machines need a lot of power, as various systems beyond the engine also burn a lot of it. As an illustration, Feeney brings up the original 2005 Bugatti Veyron (one of the 2005 cars in our above animation). The car was listed as producing a thousand horsepower, but the engine actually produced 3,000 horsepower. The car’s cooling system used 1,000 horsepower, and its exhaust used another 1,000; this left the final thousand for the engine. For the past century, almost all high-performance cars were powered entirely by petrol engines.

The new millennium, however, saw more carmakers developing alternative engines. As technology advances and the world becomes more environmentally-conscious, green power has risen to meet the challenge.

While recent years have seen a growing number of supercars embrace hybrid and pure electric engines, electric cars aren’t actually anything new.

In 1899, Belgian inventor Camille Jenatzy created the first car to reach 100kph, La Jamais Contente (The Never Satisfied). It was a fully electric one-seater missile (literally shaped like a missile, with its cylindrical body and conical nose and tail) on four wheels.

Today, Jenatzy’s legacy lives on. Formula E, which began in 2014, was the first official fully electric motorsport championship. Back on the road, new electric and hybrid supercars, such as the McLaren Speedtail, Aston Martin Valkyrie, Czinger 21C, Porsche 918 Spyder, Ferrari LaFerrari, Koenigsegg Gemera and Rimac C2 can match the top speeds of their petrol-powered rivals.

Following successful circuit testing, Valkyrie has been navigating the roads nearby @SilverstoneUK.

The team from Aston Martin and Red Bull Advanced Technologies will now begin real world testing to take our hypercar a step closer to first deliveries.#Valkyrie #AstonMartin pic.twitter.com/khQcFfKghC

— Aston Martin (@astonmartin) March 18, 2020

What a journey the McLaren #Speedtail has been. Capable of 0-186mph in less than 13 seconds, this truly groundbreaking car has seen its development programme take place all over the world, from Idiada in Spain to Johnny Bohmer Proving Grounds at Kennedy Space Center, Florida, USA pic.twitter.com/H09N56d9UW

— McLaren Automotive (@McLarenAuto) January 7, 2020

Pininfarina’s CEO Michael Perschke said, ‘electrification unlocks the door to a new level of performance and a zero-emissions future, when he announced the Pininfarina Battista, a fully electric hypercar with 1,900 horsepower (released in 2020).2

‘Don’t be surprised if someone is already out there aiming to top 500kph, and don’t be too surprised if it turns out to be electric.’

Adrian Feeney, Chairman and CEO of SAE-A

With large spoilers, air intakes and dashboard computers that track g-force, you may see some similarities between supercars and race cars. Despite the speed and handling of high-performance production vehicles, they are still remarkably different to purpose-built race cars.

Road-legal cars are often more comfortable for the driver, as race car interiors are very Spartan – designed to save weight and lower their centre of gravity for battles on the tarmac instead of cruising down the highway. Lighter and stronger materials like carbon fibre are also highly expensive and aren’t necessary for regular road use.

Luxury supercars, on the other hand, typically have comfortable leather seats and gadgets, like satellite navigation, and are designed to steal the spotlight on Sunset Boulevard. They may include exotic materials like carbon fibre to deliver uncompromised performance, and also to just show off.

Fundamentally, the car’s intended purpose changes how the car itself is designed and made. Sriram Pakkam, Motorsports Aero Lead at Ford Performance, sums it up.

‘Race cars are designed entirely around what the tyres want. High-performance road cars, and supercars even, are designed around what the customer wants.’

In the past, however, the distinction between road car and race car wasn’t always clear.

For example, there was almost no difference between the following ‘90s supercars and their racetrack counterparts:

These supercars are examples of ‘homologation specials.’ They’re the product of the homologation rules, where if a manufacturer wanted to produce a new racing car for the professional circuits, they had to produce a road-legal version first.

This often led to manufacturers producing a racing car and then making it conform to legal codes (with just enough changes to make it road-legal) to create a road-worthy supercar, before going back to designing it purely for the race track.

Now that manufacturers have access to a wider range of parts, and technology and engineering have developed further, ‘homologation specials’ have fallen out of favour.

Another key difference between race cars and supercars is weight. Dedicated racing cars are designed to be as light as possible to increase acceleration speeds, but modern fast and powerful road cars are often just as heavy as any other car. While road-legal hypercars may actually have more horsepower than dedicated professional race cars, they have a worse power-to-weight ratio, which makes them slower to accelerate than race cars.

As Feeney explains, supercars need to withstand all the forces of high speeds.

‘They need big brakes, big engines, lots of cooling equipment; everything that adds up to weight,’ he says. Today, supercars and hypercars range in weight between one and two tonnes – one of the few similarities between supercars and everyday road cars.

Beyond that, standard production cars and supercars are worlds apart.

The race for faster supercars is always speeding up with carmakers pushing the limits of aerodynamics, power and style.

Looking to 2020, Hennessey Performance is working on a new carbon fibre chassis for their Venom F5 to help propel its car to speeds of over 490.85kph (305mph), according to one Hennessey Performance spokesperson.

The Hennessey Venom F5 Just Bested the Bugatti Chiron In an Unexpected Way – The Hennessey Venom F5’s carbon fiber tub isn’t much heavier than that of the McLaren Senna #HennesseyVenom #2021 #Exotic #coupe #supercars #Exotic #coolfastcars #Cars

Read more: … pic.twitter.com/OsyNYHecbm

— TopSpeed.com (@topspeed) January 20, 2020

Reaching 305mph (490.85kph) would make it faster than Bugatti’s Chiron, which was the first car to break the 300mph barrier.

Not wanting to miss out on the action, Pagani announced a new version of the Pagani Huayra, the Imola, in February 2020. The Imola production was limited to just five cars, with a cost of AUD$8.3 million (€5 million) each at the time of writing.3

Other planned luxury performance car debuts from the cancelled 2020 Geneva International Motor Show in March4 included:

Supercars and high-performance vehicles are designed to make a statement and grab your attention. They’re all about style, luxury, performance, and being bold.

Manufacturers will continue to push the capabilities of road-legal cars to see what’s possible with science and engineering; to break boundaries, and to earn a place in automotive history. Indeed, the race for the fastest production car may never end as luxury marques and performance brands chase racing glory – and at least right now, there are exciting things to come.

Brought to you by Compare the Market: Making it easier for Australians to search for great deals on Car Insurance.